“We are told how in the beginning it came to pass that like cabbaging Cincinnatus the grand old gardener was saving daylight under his redwoodtree one sultry sabbath afternoon, Hag Chivychas Eve, in prefall paradise peace by following his plough for rootles in the rere garden of mobhouse, ye olde marine hotel, when royalty was announced by runner to have been pleased to have halted itself on the highroad along which a leisureloving dogfox had cast followed, also at walking pace, by a lady pack of cocker spaniels.” FW: 30 11-19

The encounter between H.C. Earwicker (HCE) and "the Sailor King" is a pivotal moment that contributes to the intricate tapestry of themes and motifs in the novel. Set at the beginning of chapter two, the reader is introduced to HCE, the landlord of a pub called The Mullingar House, located in Chapelizod. HCE gets his name from an amusing incident that took place while he was tending his garden.

As HCE diligently tended to his cabbages in his garden he found himself plagued by earwigs. In an unexpected encounter, a character referred to as "the Sailor King" stumbles upon HCE in his garden, observing him carefully plucking the earwigs off his crops. Filled with amusement at the sight, "the Sailor King" spontaneously decides to nickname him an "earwigger" due to his peculiar activity.

This encounter proves to be significant in shaping HCE's identity and subsequent name, which evolves into Earwicker, reflecting the whimsical nature of wordplay and transformation that is prevalent throughout the novel.

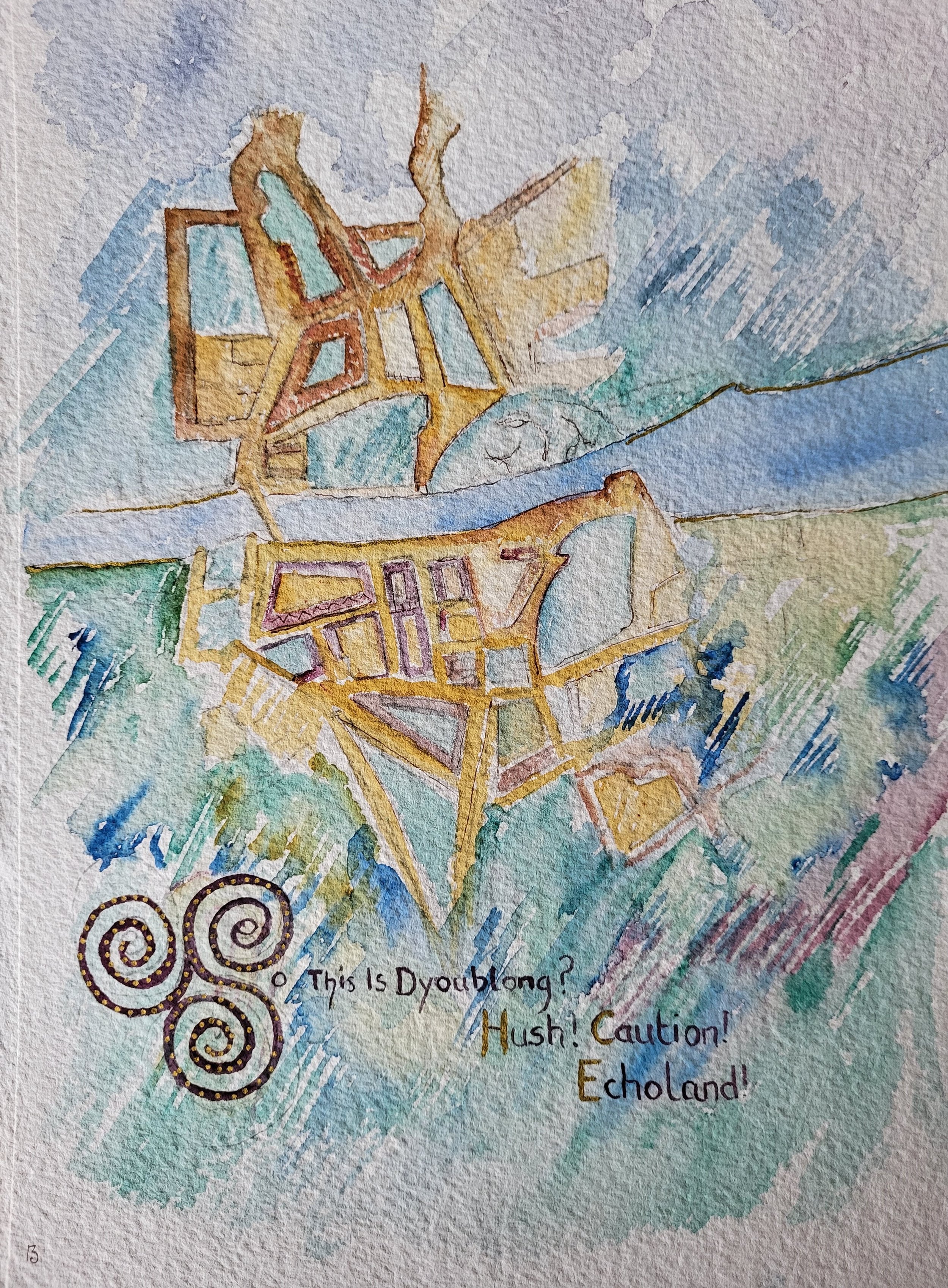

The background illustration for this chapter is based on an OSI historic map, depicting Chapelizod and The Mullingar House pub, which has a rich history as a coaching inn, serving food and drink for over three centuries.

Throughout "Finnegans Wake," recurring motifs such as oranges on the green ("Iris Trees and Lili O'Rangans") and the hunter and prey dynamic come into play, adding layers of complexity to the narrative. Additionally, HCE's seven items of clothing, introduced earlier in the novel, resurface, providing continuity in the constantly shifting narrative.

Joyce's masterful storytelling weaves together these various elements, creating a dense and labyrinthine narrative where the tale of HCE and the Sailor King represents only one of many interconnected threads. "Finnegans Wake" is a rich tapestry of language, history, and myth, retelling itself endlessly, and never repeating exactly, making it a unique and challenging literary work for readers to explore and interpret.